La Perla is a shanty town sloping into the sea in Puerto Rico. Spotlighting the “culture of poverty”, it was this town that Oscar Lewis made famous in his book, La Vida, published in 1965. Mark Allen visited La Perla to see whether the picture had changed from that portrayed so vividly 11 years ago. He found it to have a compelling vitality and gaiety

which contrasted with its poverty

ON A SATURDAY morning in May, 1964 Rosa Gonzalez went into La Esmeralda to spend a day with Fernanda Fuentes. It was about half-seven. She approached the slum by way of the paved road, then walked down through the short tunnel that had been cut out of the old fort. The tunnel led directly to an open space that served as a plaza, a bare paved area without flowers, bushes or trees. A long cement bench standing against the first wall was used by people of the slum to rest, to visit with their neighbours, to wait for-a taxi or an ambulance or to watch a large public TV set which had been placed there by the municipal government. Television watching went on day and night. Near by were a few small bars and the office of the Popular Party of Munoz Mavin, where flags and posters were displayed.

Twelve years later, at 11.30 am on Thursday, July 15, 1976, to be precise, Rosa Gonzalez made very much the same journey and saw very much the same kind of scene as that described in the opening chapter of Oscar Lewis’s famous book, La Vida. She walked down the short tunnel to the plaza where people were milling around, watchful. This time there was no public television but music seemed to pound out from every door. Blue and red flags and posters were everywhere, the colours of the two major political parties the Popular Democratic Party and the New Progressive Party, signifying the advent of the primary elections. This time Rosa was accompanied by me.

La Esmeralda is the pseudonym given to La Perla, the shanty town located on the steep seaside banks of old San Juan, separated from the city by the thick wails of a Spanish fort, whose character and people were portrayed so poignantly in La Vida. Rosa Gonzalez is the name Lewis gave to Muriente Paguita, then a sociology graduate at San Juan University, who spent six years of her life researching Puerto Rican families in San Juan and New York in order to record first hand the lives of people caught up in what Lewis termed “the culture of poverty’. La Vida, published in 1965, was to be the first in a series of volumes based on a study of 100 families but due to the death of Lewis in 1970, the-other books, one of which was almost complete, have never been published.

Rosa collaborated with Lewis throughout and was Lewis’s principal research assistant. Certainly without her, La Vida would never have been written or certainly not in the form it was. The book records in 669 pages the movements, language, hopes and fears of the Rios family, whose five principal characters consisted of the mother, Fernanda, two married daughters living in La Perla, Felicita, aged 23 and 19-year-old Crux, plus a married son, Simplicio, aged 21, and daughter, Soledad, aged 25, living in the Bronx district of New York. Rosa is the camera’s eye, capturing their attitudes and language with a refreshing vividness that has made La Vida read like a first-class novel. Now Rosa is not only the observer, she is intrinsically caught up in the film itself. She returns to La Perla, at least once a week, to give help and advice to the people in organising their communities.

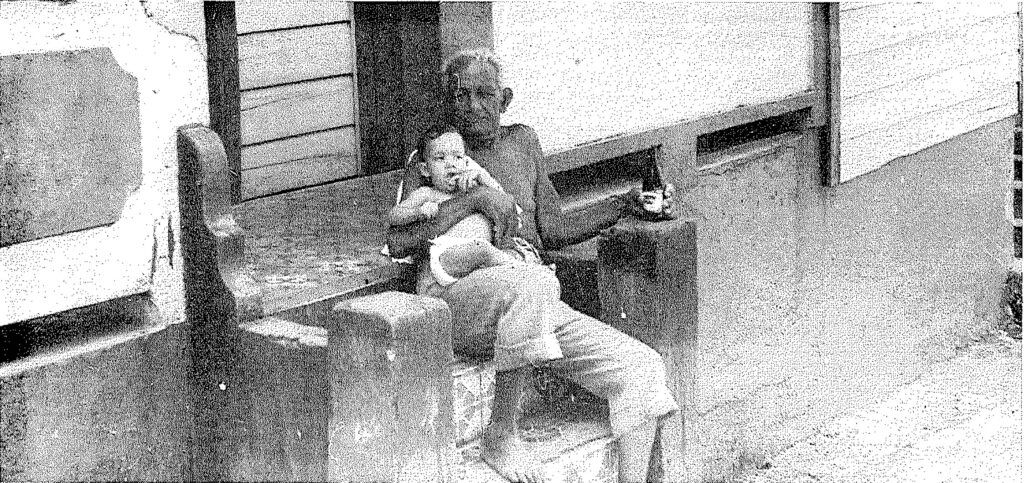

Only residents of La Perla would recognise the physical changes which have occurred in the past decade or so. Many houses are now built out of a mixed construction of concrete and wood; instead of just wood and running water, electricity, waste disposal facilities and paved alleys. are now commonplace. Essentially, however, La Perla is very much the same as it was.

It is difficult to believe, as we walk through the plaza on this bright July morning, that La Perla is supposedly a hostile, violent, unattractive place; a place where murder, theft, drug pushing, prostitution and poverty all co-exist, a place to which the average middle-class Puerto Rican will never venture. But I walk with Rosa and the day before yesterday I walked with Lois Soto, a community worker in La Perla, who is again much respected by the people. On my first day in Puerto Rico as I and other British colleagues were sightseeing near to the old fort, a policeman followed to warn us against going any further towards La Perla. A dangerous place, he said, cutting the air with his hands and pointing at my camera.

There is a vitality and fearful excitement to the shanty town which I find gripping. Indeed, almost an elegance. La Perla is a labyrinth of about 900 houses, in which about 3,600 people live. Many houses are tightly packed together separated only by narrow alleyways. It forms part of a harrow rectangle, only a few hundred yards long which is very much a small community of its own with a cemetery, church, school, community centre and many bars. The many sounds emanating from radios, jukeboxes and television give an atmosphere of gaiety to the whole place which is reinforced by the many brightly- painted murals in drab walls, La Perla — “The Pearl?’ — is almost a contradiction.

The physical condition of the houses in La Perla becomes lower and lower the hearer one descends to the beach. So, too does the social status of the people. Those living nearer to the beach are generally the poorer, more deprived and criminal elements. The beach, which is filthy and scattered with driftwood and old junk, has two useful functions for the people living near it. On it pigs are bred because of the abundance of garbage. It is also a good escape route from the police. However, it is a dangerous place because of the constant threat of high tides and although many of the houses nearest to the beach are built on stilts, this is only an elementary protection against really rough seas.

To walk with Rosa, or more correctly, Muriente Paguita, this slender, elegant woman of 35 who has given so much of her life to the people of La Perla, is to become totally immersed in the way of life of the shanty town. To watch her talking to the people and to listen to her story says as much to me about. love and human understanding as one is ever likely to hear. She is a woman of humility, of dignity and sincerity and the people love and trust her.

How had she managed to win over the people so completely? ‘When I first went to La Perla I took my notebook and made notes, but the people although they talked to me they never tell me the truth. So for six months I played with the children in La Perla and after a while the mothers start asking me into their homes. One day I fall ill and I stay in a hotel in San Juan and some people come and said to me ‘Muriente, you are a good person, you should live with us in La Perla and not in this dangerous place San Juan.’

‘So I went to stay in La Perla. I played with the children and helped the families with the pigs. One day someone said to me why you stay with us, you area student at the university.’ I then tell them the truth as to why I am in La Perla. I say that I think it is important for the world to know the reality of La Perla because there is much goodness. ‘For some time I share a room near Crux. We share the same bathroom. Later some people they came and said to me ‘Muriente, if you are a government agent you must tell us and we shall see that you leave safely. Please tell us the truth because if- we find out later that you are an agent you will destroy us and all that you -have done for us.’ I said to them: ‘I promise you I am no agent. I come from a ‘poor family and lead a poor life like you. I shall stay in La Perla’. So I lived in La Perla for one-and-a-half years sharing the same life with the people.’

Oscar Lewis in the introduction to La Vida expounded his theory about “‘the culture of poverty’’, the way of life that tended to flourish among the poor under a certain set of conditions. Lewis listed these as a cash economy, wage labour, and production for profit, a high scale of unemployment; low wages; the failure to provide social, political and economic organisation for- the low income population; the existence of a ‘bilateral kinship system and finally, the existence of a set of values in the dominant class which stresses the accumulation of wealth and explains low economic status as the result of personal inadequacy or inferiority. The culture of poverty was both an adaptation and reaction of the poor to their marginal position in .society. It represented an effort to cope with feelings of homelessness and despair. Certain traits were evident, in their more positive form a capacity for spontaneity and adventure and an enjoyment of the sensual.

Such characteristics are displayed by the family in La Vida as they are in La Perla as a whole. All members of the family talk in a language that is simple, direct and earthy. Violent behaviour is quite common. Members of the Riós family have an impulsive zest for life and an overwhelming preoccupation with sex. Sexual relations tended to be open and prostitution was rife. The five major characters had had between them 20 “‘marriages’’, 17 of which were consensual and only three legal, Fernanda and her two elder daughters, Soledad and Felicita, had all at one stage or another been prostitutes. Indeed Lewis went as far as to say that about one-third of all households in La Perla had a history of prostitution.

Many Puerto Ricans are extremely hostile and critical about the picture that was painted in La Vida. They claim that, Lewis exaggerated the extent of poverty and in particular, prostitution, in order to advance his theories about “the culture of poverty”.

Community worker Lois Seto, aged 26, who is based in La Perla at a multi-purpose community centre, is one who shares such feelings. Lois said as he showed me around La Perla, two days before I met Muriente: “La Vida is a complete lie. Oscar Lewis used prostitutes to talk to people in La Perla. He hardly came to La Perla himself. He describes the Puerto Rican woman as a prostitute but there’s a big difference between a prostitute and a woman who lives with a man. I don’t think La Perla women are selling their bodies. Poverty is a problem but no one is starving. Most people earn between $240 and $400 a month (£135 to £222). Those that are out of work can get public assistance and food stamps. There are some drug addicts and pushers around and last year there were two killings; both were addicts. However, since I have been here I have never been threatened. The people love me. They are much more suspicious of outsiders. I would say alcoholism is our biggest problem here but La Perla is still one of the best places to live.”

Lois introduced me to Rosa Colon who has lived in La Perla for 35 years and helps out at the community centre. She shares the house, consisting of three bedrooms, a living room, dining room, kitchen and inside lavatory with her husband, two daughters, son, daughter-in-law and grandson. The living room, the only room I visited, with a TV set dominating, was comfortably furnished, Her daughter-in- law was 18 and had, I was assured, been legally married since she was 14. Since this was the only family in La Perla who allowed me into their home it is difficult to draw any conclusions.

I put to Muriente, who is now the director of a multi-purpose community centre at Sabara Abajo, about 15 miles from San Juan, some of the criticisms made by Lois Soto about La Vida, and about Oscar Lewis, namely that he had used people to elicit an erroneous and exaggerated picture about La Perla. She smiled: ‘‘All I can say is that we had to deal with real situations. It’s better not to say anything else. But the people love Oscar. ‘Many of them have pictures of him in their homes. When Oscar was presented with an award, two of the family went with him to New York to receive it. All the money was spent on the family.” Prostitution? ‘Yes, it still goes on in La Perla.”

Muriente believes that La Vide helped the family, now all based in New York, to believe in itself and points to the fact that Soledad is now a nurse and Simplicio owns a garage. She agreed with Lois that La Perla has very many strengths and says that the people are now much more united and community orientated than they ever have been, although she says this had nothing to do with the publication of La Vida. People who leave La Perla want to return.

This is borne out by a visit we make to see a family of 10 now living in a municipal housing project for poor people at Ramos Antonini, quite near Mauriente’s community centre. The whole estate is a maze of grim and forbidding blocks of flats which are far more oppressive than La Perla. The mother, with no husband to support her, receives $35 a month on public assistance and pays $24 a month for the three-bedroom flat. If it were not for the fact that her two sons are both working and help to support her she would never be able to manage.

Her background is fairly typical of many of the people whom Muriente has studied. Born in the country, she drifted to La Perla where she became a prostitute for several years. She then moved to New York, where she lived for many years before returning to eke out a humble living in her caserio. One of her sons is a heroin addict. Although the interior of the flat is pleasantly decorated and furnished, the mother — like a great many poor Puerto Ricans she possesses an abundant supply of clothes — still hankers after returning to La Perla. Without wishing to glamorise a slum it would be wrong to deny that La Perla does not have a way of life that offers a great deal of support to families trapped in the so-called ‘‘culture of poverty’’.

The ‘‘culture of poverty’’ in Puerto Rico is not unique is La Perla. Nor is La Perla the worst example of Puerto Rico’s slum belt, Martin Péna having that dubious distinction: What is important to point out is that the conditions under which poverty and the culture of poverty exist are rife in Puerto Rico.

In advancing his hypothesis Lewis said that the culture of poverty developed most frequently when a stratified social system was breaking down, as in the case of the transition from feudalism to capitalism or during periods of rapid technological change. Both politically and economically Puerto Rico, a small, densely populated island of 3,100,000 has seen considerable change since the last world war.

At the heart of Puerto Rico’s dilemma has been the constant conflict between cultural identity and the search for economic survival. On the one hand, it enjoys a Spanish culture and language. On the other hand, economically it depends on the United States. This conflict is reflected in its own political status. A former US colony, in 1952 it entered a “commonwealth”? form of relationship with the United States which, in effect, gives Puerto Rico considerable political independence. For example, Puerto Ricans elect their own governor and focal legislature. The two major political parties, the Popular Democratic Party and the New Progressive Party, base their platforms on their relationship with the USA, the former wanting to maintain the commonwealth, the latter wanting Puerto Rico to become a state of the USA. Together they command about 80 per cent of votes.

Political changes have been accompanied by massive technology. Before the 1950s agriculture was far and away the biggest industry but, as a result of ‘‘Operation Bootstrap’? there was a tremendous expansion of industry. By the end of the decade manufacture had replaced agriculture as the biggest industry. At the same time there has been a concomitant increase in prosperity and the emergence of a powerful middle class. Certainly, Puerto Rico with its lush hotels and its big American cars winding their way through constant traffic jams, gives the appearance of affluence. But if anything the gap between the very rich and very poor has widened. In 1953 the poorest 45 per cent of Puerto Rico’s families earned only 18.2 per cent of total income, in 1970 this dropped to 16 per cent. According to the latest government figures, the average family of five requires an annual income of $5,700 a year for its basic needs. However some 35 per cent of the population earn only $2,000 a year. At the moment over 17.1 per cent of the population is unemployed but the unemployment rate has. been as high as 21 per cent. At the upper end of the scale some 43 “tax units’ have gross incomes of $150,000 or more a year.

As many as 60,000 families are dependent on welfare payments (aged, disabled, blind and dependent children) and over half the island’s population also receive Federal Food ‘‘stamps’’. These can be converted into food products for people on public assistance, patients in medical and mental clinics, children in day care centres and students. However, according to no less an authority than Puerto Rico’s Secretary for Social Services, Ramen Garcia Santiaga, the level of benefit is “inhuman’’. For example, an average, elderly person ‘receives only .$18.50 a month, a blind or disabled person $13.50 and an average family only $46 a month.

it was Mr Santiaga who told me: “We would need to double or treble our funds in order to take care of the basic needs of people on assistance.’ Indeed, Puerto Rico is campaigning for the USA to increase its contributions to welfare funds by an additional $160-$200 million. In particular, the Government feels aggrieved that Puerto Rico has not been included in America’s much more generous and comprehensive Supplement Security Income Programme.

Back in La Perla, only 10 minutes away from the Governor’s Palace and the heart of old San Juan where tourists flock to see the sights, little boys play with the garbage on the beach; mangy dogs growl out their warnings; alcoholics lic on pavements out- side the bars. Meanwhile, as Rosa Gonvalez walks the same streets of La Perla as she has for the past 12 years or 60, smiling faces stare out of blue and red posters. The primary elections may now be over. The ruling, pro-commonwealth Popular Democratic Party may have done very well. But for the people of La Perla life will not change overmuch. The plazas will still pulsate with a cacophony of sounds. And the sea will still sigh.

Written 1976