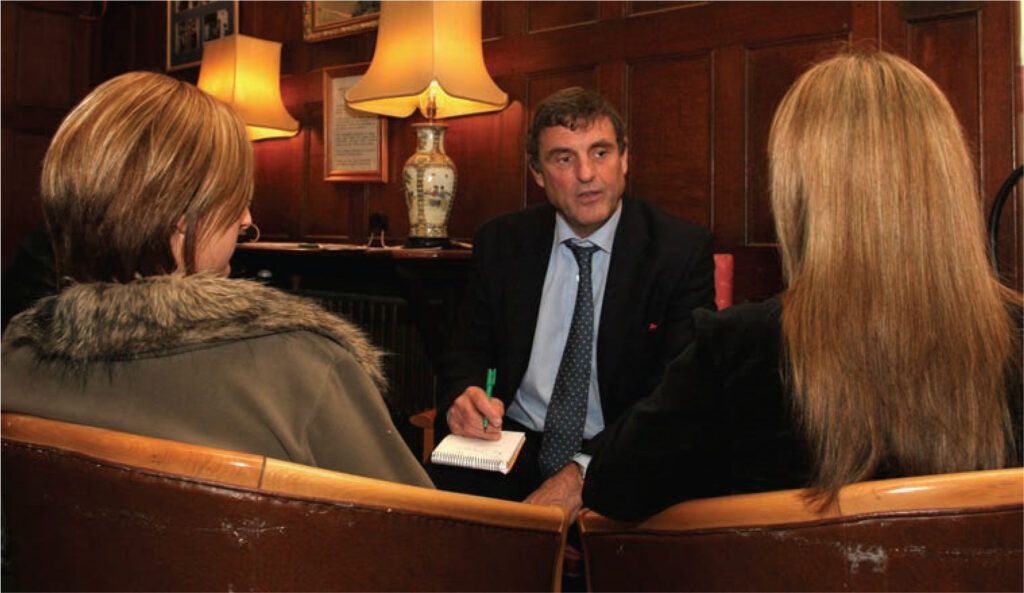

Christmas at Clouds, the drug and alcohol dependency centre that once treated Robbie Williams, will be as jolly an affair as possible. Editor Mark Allen makes the journey to this country house and meets its inspiring staff and patients.

The road to Clouds House is paved with glimpses of gold and good intentions. The journey from the village of East Knoyle climbs along a dark country lane, surrounded by woodland, brushed now by the colours of autumn.

At a crossroads you turn sharp right and then almost immediately the same again into a short drive in parkland. On my first visit two deer shot across the road, nearly colliding with my car.

Then you come upon the house, late Victorian and quite unprepossessing compared to many grand country mansions; tucked away and angular, it takes a sideways and understated glance at the outside world.

This journey is the one that every patient will make when coming to Clouds House and it seems oddly apposite, a metaphor for what is to come; an uphill struggle against the demons at bay; a crossroads in a person ’s tormented life; a chance for sudden and unexpected insights in an atmosphere that is calm and non-judgemental.

This Christmas, as always, will be as jolly an affair as possible. There will be singsongs and a sketch prepared by the patients, with staff members afforded nicknames and gently ribbed. Every patient will be presented with a present by the staff. At least this year the patients will be able to take part in the festivities. Last year many of them will have been too blotto to remember what went on.

Clouds House has a somewhat chequered past. Designed by the renowned architect Philip Webb, the house was built in 1883 as a country home for the Wyndham family and it was assumed that it would remain the family ‘s rural retreat for generations, housing their unique collections of art treasures.

However, in 1924, only 13 years after Percy Wyndham’s death, the house was let to strangers. Then in 1937 the estate was broken up into smaller plots and Clouds House was sold to a retired barrister from Wimbledon.

“We need to challenge the thoughts, beliefs and behaviour of addiction”

The ensuing years have been a battle & for survival, the house more than once being threatened with demolition. In 1944 Clouds House was acquired by the Church of England’s Incorporated Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays, now known as the Children’s Society, and became a nursery for unwanted babies until 1964.

During this time the total number of children admitted, of whom around 42 could be housed at any one time, was 534. Of these, 376 were found adoptive parents, 63 transferred elsewhere, 93 returned home and two died.

Attitudes to accommodating homeless children in large country retreats had changed by the 1960s and, anyway, Clouds House was a massive financial drain. Once more the house was up for sale; this time Colonel Stephen Scammell, who already had a stable block next door, became the proud owner. He acquired the property for £24,000 in the name of the McLaren Foundation.

After the completion of necessary repairs and decorations, a frantic search for tenants ensued. For a time it became home and school for about 50 maladjusted boys but it was badly knocked about.

In 1983 fate took another turn when Clouds House was purchased by The Life-Anew Trust, which had been set up the year before by Peter and Margaret-Ann McCann, who are no longer involved with Clouds but run a similar treatment centre in Edinburgh, and so began its new life as an alcohol and drug dependency treatment centre. Since then more than 8,000 people have been admitted, including some famous celebrities — the pop star Robbie Williams being about the best known of its ‘alumni’.

There are today four main branches to Clouds, which is now administered by the Clouds charitable trust: Clouds House itself, which is a residential treatment centre for up to 38 patients suffering from drug and alcohol dependency; Families Plus, a range of therapeutic support services for family members; and Clouds Community Services, based in Bournemouth, which includes a pre-treatment group, a structured day programme and a skills-based training scheme, known as Working Recovery. The fourth branch is Clouds PETR (Professional, Education, Training and Research), which offers a foundation degree in addiction.

My journey to Clouds House for the purpose of writing this article began after meeting Nick Barton, the chief executive and a clinical psychologist, at a friend’s birthday party where I expressed an interest in visiting Clouds. As a student, many years ago, I worked for a few months in a London remand centre. I became intrigued when the very first heroin addict the remand centre had ever accepted walked through its doors.

Since then I have known many people destroyed by addiction, mainly drink. I have belonged to a profession — journalism — with one of the highest incidences of alcoholism. I can recall the sadness I felt when I drove the former Campaigning Journalist of the Year, now long dead, to a treatment centre, a bottle of whisky secreted in his belongings.

So, after a reasonable length of time, during which it was necessary for me to visit the centre to establish the ground rules for writing this piece, I am back at Clouds House, to be met by Claire Clarke, the slim, elegant and personable head of treatment services, herself a recovering alcoholic.

Claire has been ‘clean’ for the past decade, having courageously and successfully fought her own private battle against drink and drugs.

Claire, who joined Clouds as a counsellor in 1998 after gaining a post-graduate diploma in addictions counselling, is a passionate advocate of Clouds: “I feel proud to be part of Clouds. Our aim is to help patients through recovery. Changing behaviour is a very traumatic and difficult process but recovery is full of hope.

“We need to challenge the thoughts. beliefs and behaviour of addiction and find a way to change. One of our jobs is to dismantle the walls surrounding addiction, coping skills and defence mechanisms, and then rebuild them.”

Indeed, one of the impressive aspects of Clouds is that many, although not all, of the staff are recovering addicts. An addict, whether of drink or drugs, or as is commonplace these days, a combination of both, is never ‘cured’, even though they may have been abstinent for many years, there being no recognised ‘cure’ for addiction. Addicts must always remain in a state of ‘recovery’, one of the hardest lessons.

What causes addiction? There are no simple answers. Many alcoholics and addicts come from dysfunctional families and they are often intelligent, creative and sensitive. They have addictive personalities and they are prone to risky behaviour. Alcoholism or drug abuse often runs in families, suggesting also a genetic predisposition. There is sometimes a traumatic event that triggers addiction.

Claire reports to Kirby Gregory, who as the head of client services has overall responsibility for all of Clouds’ direct- to-client services. Under Claire’s overall umbrella at Clouds House are admin and hotel services, and the nursing and counselling teams, all three of which have their own separate managers.

Altogether there are more than 60 full-time and part-time staff who work at Clouds House. It has as its medical consultant Dr Gordon Morse, a single-handed GP in nearby Fovant and an expert on addiction, as well as his assistant, Simone Yule, a GP from Shaftesbury. A consultant psychiatrist is also on hand.

The not-for-profit charity as a whole generates around £3 million a year in revenue and trims its cost budget accordingly. It has least by providing a gym facility.

Around 75 per cent of the charity’s income comes from public funding from government, local authorities and health trusts. The rest comes from private fee-payers, who are charged £9,240 for the six-week treatment course, and from private donations.

The patients, of whom there were 32 when I visited, share two or three-bed rooms. It will be their home for the next 42 days, providing they can last the course, which the majority, more than 60 per cent, are able to do.

Most patients will arrive highly intoxicated on drugs or drink, although bringing drugs or alcohol into Clouds House is strictly forbidden. Many will be in a dreadful physical and mental state. One of the first tasks is for them to be assessed and treated in the medical centre by Alan Mead and his team of 28 full-time and bank nurses and 15 regular and bank nursing assistants. They run a 24-hour, around the clock service, providing crisis intervention and physical, emotional and psychiatric support.

Alcoholics will normally go through a five to seven day detox in which they will be prescribed Diazepam to relieve withdrawal symptoms and help them sleep. For opiate addicts the detox programme is 12 to 14 days in which a combination of different drugs will be prescribed to wean them off the drugs they have been abusing and give them a ‘softer landing’. There are a small number of patients addicted to prescribed drugs, like Valium, who will require a different treatment regime.

Patients immediately will start an intense programme of group therapy and activity, provided by the counselling team, in which the help and support of other patients is a fundamental part of recovery. The approach follows the 12-step programme in which patients are encouraged to accept they are addicted and take responsibility for engaging in an integrated and holistic approach to treatment on their physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual levels.

I attended an afternoon lecture by John Wood, the counselling team leader whose team comprises three senior counsellors and six counsellors. There are currently also three counsellors in training who are in the process of completing Clouds’ own training.

All patients attended the lecture, which was often laced with their own witty and self-deprecating interjections. John, himself a recovering alcoholic, wrote on the board “Get a life!” and asked: “How do you enjoy yourself after drugs?” He then asked the group to examine some wrongly conceived concepts such as “I can’t have fun if I’m not pissed/stoned?” or “I have no confidence if I’m not on something” before attempting to debunk such views. He stressed: “No one has died from lack of confidence. Lots of people have died through alcohol.”

It was encouraging to meet a group of four former Clouds House patients, who had undergone treatment in the past few months and who come back for after-care support picture of health, in contrast to one or two of the current patients who looked emaciated and physically unwell.

These ex-patients were young, articulate and intelligent, impossible to separate from other people in the crowd. Before their addictions had taken hold, they had had jobs in IT, the on-line media, one was an air stewardess and one was even a therapist. The air stewardess, who is soon to start flying again, told me: “I had the best time ever when I was at Clouds House, there was so much laughter and fun.”

However, each of these former patients knows, that their battle has only just begun. It is a day-by-day, lifetime battle to keep sober or clean with a 60 per cent chance of success. Independent research conducted in 1995 established that roughly one third of all Clouds House patients were free of alcohol and drugs 30 months after treatment, one- third had relapsed but were back in recovery and one-third had relapsed and were back in addiction.

Clouds House provides patients with the hope that they will be able to spend a life free from alcohol and drugs. It gives alcoholics and addicts a chance for a future. As I made my way home down the lane to East Knoyle I could not help noticing that the sun had come out and the day seemed brighter and less grey than when I had arrived. I started humming the words of The Rolling Stones’ hit: “Hey, you, get off of my cloud.” For some reason these words & seemed appropriate.

Written 2004